The true culprit: virus or poverty?

Author: Queenie Li, Researcher of Our Hong Kong Foundation

The pandemic of 2020 spurs us to reflect on the essence of our public health system. When asked to define health, most people are likely to associate it with being free from chronic conditions and independent from long-term medications, whilst maintaining a robust immune system. In recent years, more attention has been paid to the balance of physical and mental health, expanding our understanding of health from physiology to psychiatry. Yet beyond the binary of matter and mind, public health is shaped by a panoply of social determinants of health.

Back in 1948, the founding year of the World Health Organisation (WHO), it declared in its constitution, ‘Health is not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition.’ Led by prominent public health expert Sir Michael Marmot from the University College London, the WHO’s Commission on Social Determinants of Health has been striving to mitigate health inequalities by improving the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age. Its mission spans out of the specialty of health care with a more integrated scope involving education, housing, climate change, clean water and beyond. Its Heath-in-All approach urges governments around the world to thoroughly consider social determinants of health when formulating and implementing policies in all fields.

The notion that everyone should have equal access to quality health services sounds fairly simple and perhaps clichéd, but as we find ourselves in the 21st century, Universal Health Coverage is still commonly out of reach. As coronavirus rips through the world, a local rough sleeper, when interviewed by the media, said ‘poverty kills, as much as the pandemic’. Truly sobering, examples of health inequalities are ubiquitous locally and internationally including our neighbor Singapore.

Ignoring health inequality will foil our fight against the pandemic

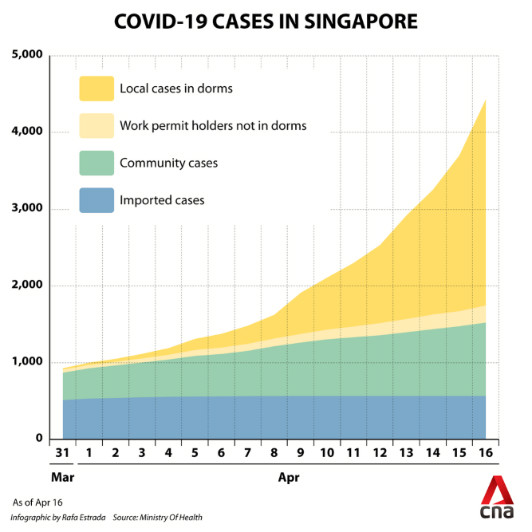

When Covid-19 first broke out, Singapore’s decisive and timely measures, the government’s rigorous contact tracing and the prime minister’s regular public addresses earned the city-state international applause. However, in April, Singapore experienced a dramatic spike in cases, with over 1,000 new confirmed cases each day at its peak. More than half of its cases being migrant workers, the collapse is none but the brutal consequences of neglecting migrant workers’ rights, a problem that has long been overlooked by the rest of the society. The non-profit organisation ‘Transient Workers Count Too’ identified four indictments: these migrant workers are crammed into small dormitories; they are packed into the back of lorries for commuting; a culture of avoiding sick leave for fear of being axed; and their meagre salaries make it unaffordable to take days off even unwell. As a result, this group of the population are particularly vulnerable to the risk of infection and lack the means of self-protection. In many scenarios alongside this, we cannot solely rely on health policies to address what presented as a public health problem. The breakdown of protective mechanisms for one group due to other social determinants will ultimately cause an outbreak in an entire country.

At the bottom stratum of Singapore’s society are over 200,000 low-wage migrant workers living in mega-dormitories. Meanwhile, Hong Kong has more than 200,000 people living in cage homes, coffin cubicles, rooftop slums, subdivided flats or sleeping rough on the streets. The epidemic unveiled and even magnified the ugly truth of our income inequalities: whilst some are stockpiling protective gears shipped from overseas, others are steaming and reusing their only face mask; whilst some families are savoring home workouts in their spacious homes, other families are trapped in small apartments that leave no breathing room in case of conflicts; whilst some have the leisure to cherry-pick virtual backgrounds for a conference call, there are students who have to wait their turn to use the family computer for online lectures. As our communities join in the fight against coronavirus, it is delible that staying safe ourselves is no longer enough to keep the virus at bay. A life of health should be made a fundamental right to all.