Elderly-home restrictions must be eased to boost supply

This article appeared originally in the China Daily on 18 August, 2022.

Authors: Dr. Stephen Wong, Senior Vice-president and Executive Director of Public Policy Institute, Our Hong Kong Foundation, Calvin Au, Assistant Researcher at Our Hong Kong Foundation

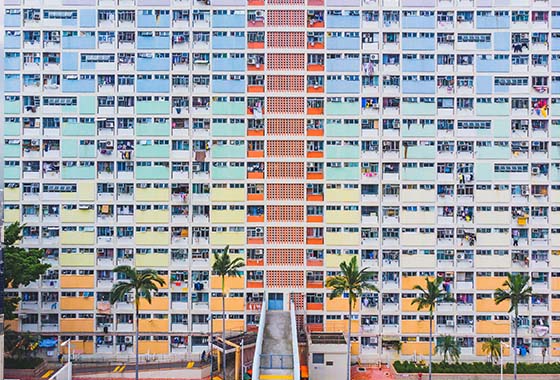

Hong Kong is hounded by both a housing shortage and deficit in residential care homes for the elderly (RCHEs).

Approximately 60,000 of 1.5 million senior citizens aged 65 and above reside in care homes, according to the Census and Statistics Department. Meanwhile, a backlog of more than 20,000 applicants who wait an average of 3.6 years for accommodations in subvented and contract homes remains. Worse still, private nonsubsidized homes vary in quality and are among the most cramped. Such undesirable living conditions for the elderly are worrying, particularly after the fifth wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, which saw countless residents infected and further highlighted the urgency of providing proper housing for the elderly. The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region government must find new ingenuity to enhance its working efficiency. Only by fully harnessing social and market resources to boost supply of residential care homes for the elderly can we ensure that the elderly will live their twilight years in comfort.

While the government has come up with proposals to increase RCHE places in the coming decade by approximately 10,000, the success of its plans depends on the availability of various land sources that are not without hindrances. For instance, the government has proposed reserving 5 percent of the gross floor area of public housing projects for that purpose where it is appropriate, and to incorporate such land lease conditions in land sales to make it compulsory for developers to construct residential care homes for the elderly in such projects. The bundling of RCHE and public/private housing projects comes with a drawback — housing-project delays will ripple through related RCHE projects, constituting a lose-lose situation of interminable delays.

The government should capitalize on social and market forces to increase RCHE places. Unfortunately, non-governmental organizations and private developers are discouraged by three major obstacles: 1) unreasonable height restrictions limiting land development potential; 2) the long processing times for approval and; 3) a lack of incentives for private developers.

The Residential Care Homes (Elderly Persons) Ordinance requires no part of an RCHE can be situated more than 24 meters above the ground floor, so the time taken to rescue residents with mobility problems can be shortened in an emergency. The rationale behind this law in this regard seems frail since hospitals with physically impaired patients are not held to the same height restriction. Singapore never had RCHE-specific height restrictions despite a higher population density. It’s safe to say the 24-meter restriction lacks a sound scientific basis.

The government has implemented two limited exemptions: 1) The Social Welfare Department can relax height restrictions of individual RCHEs on a case-by-case basis in consultation with the Fire Services Department for nondormitory areas such as kitchens, laundry rooms, general offices, and staff areas; 2) Tseung Kwan O Area 72 Welfare Community Complex is an RCHE pilot project 24 meters above the ground with improved building safety designs such as open balcony corridors to facilitate horizontal evacuation.

That said, the sector generally dislikes the piecemeal adjustments and the slow progress of the two measures. Nondormitory areas should be entirely exempted since they do not affect the evacuation of elderly residents. Meanwhile, the Tseung Kwan O pilot project will not be completed before 2029. Such a slow pace is hardly acceptable.

The government should disclose the pilot project’s design parameters to the care-home service sector while publicizing design guidance and approval criteria for upper-floor RCHEs. Specific requirements for site area, construction materials, passages, elevators and refuge floors, as well as the special designs and manpower needed for horizontal evacuation, should be clarified. Non-governmental RCHE pilot projects should also be allowed to more fully utilize land resources.

The government launched two phases of the Special Scheme on Privately Owned Sites for Welfare Uses, in 2013 and 2019. The program sought to encourage better use of land owned by nonprofit organizations through expansion, redevelopment or new development. More diversified welfare facilities, including elderly service places, are expected on privately owned sites. Relevant costs are covered by the Lotteries Fund as an incentive. Only six projects have been completed, offering a paltry 260 elderly service places. Among Phase One’s other 44 projects, many remain under construction, in design stages, under technical feasibility study, or pending feasibility study commencement. The progress of Phase Two has yet to be disclosed. Understandably, nonprofit organizations specialize in service provision but not in construction projects, but the Social Welfare Department should be much more proactive in facilitating applications and construction.

The government announced the Scheme to Encourage Provision of RCHE Premises in New Private Developments in 2003. Eligible RCHE premises are premium-free while construction costs are borne by private developers, which are entitled to ownership of the RCHEs upon completion. Only one such project, in Tuen Mun, has been completed so far, while three other applications are still mired in land administration procedures. Activity in the overall market is sluggish. The industry consensus is that the RCHE premium exemption is unappealing for developers because of meager profits from elderly residential care services because of the exceptionally high operating costs, particularly for employing staff with the right expertise and experience. The government needs to increase the incentives.

More than a quarter of the Hong Kong population will be above 65 years old within a decade, and greater demand for RCHE places is inevitable. In view of the current unfavorable living conditions in most RCHEs, the government has expanded the per capita net floor area through the Enhanced Bought Place Scheme and legal amendments at the Legislative Council. Be that as it may, more spatial supply is needed to enhance the living conditions in RCHEs. Hong Kong’s aging demographic brooks no delay in increasing RCHE supply. It’s high time the government thinks outside the box to boost its working efficiency and fully deploy social and market resources in this respect so that the city’s elderly can live dignified lives.